Pavlodar, Kazakhstan 19 June 2016

Outside, behind the windows lies the incredible vastness of the Kazakh steppe. Not a tree in sight, only the blurred line of hills far away. Here and there a herd of horses or cows, a pray bird, and the occasional dusty road. At the moment, however, we cannot see any of this, because the windows of the bus, our last hosts maneuvered us in, are hung shut with curtains. With our deep dive into the Kazakh culture form the day before, the orange curtains come as a welcome change. More on that later, because much has happened on our way here.

We return to Moscow. After hopping and jumping over various motorway crossings, we continued our journey east. First with Olek, a self-proclaimed Russian gangster. We did our best to try and ignore that, to not get involved in any dubious business-deals, and tried not to pay too much attention to the self-made tattoo on the palm of his left hand. Except for the somewhat aggressive style of driving, we felt safe with Olek. Perhaps as he seemed impressed by our fearlessness (we jokingly refered to it as stupidity) to sleep in the wild with our small palatka (tent) between the medved (bears).

Not soon after we would have our first night sleeping behind a petrol station. Not a bear in sight, but plenty of mosquitos militantly buzzing around our heads, forcing us to set up our tent in record time without any discussion on the required amount of tent pegs.

Unfortunately we couldn’t find coffee at the petrol station the next morning, but instead we found Vladimir, who drove us slowly but steadily in a convoy with two trucks to Cheboksary. In no less than 19 days(!) Vladimir accompanied the trucks with farming equipment from the Netherlands to Vladivostock! Why he was driving alongside them in his car we weren’t able to figure out.

We decided to go further south and when we parted ways we camped out beside the motorway once more, luckily without any unwanted visits by bears or wolves. The next morning we met the wonderful Renaz and John who drove us with great enthusiasm to their home town Chistobal, where we were invited by Renaz’ mother to have traditional Tatar sweet and savory delicacies. With their friend Lera, who spoke fluent English and could answer our many questions, we walked around the smallish city. We learned that Tatarstan is the strongest economical region in Russia, with their own language and a 50-50 divide between Muslims and orthodox Christians.

We were invited to stay with Lera in the beautiful Russian-style wooden house of her aunt and uncle. While Lera was doing a top job translating the stories of her aunt from her travels when she was young, we were enjoying the homegrown strawberries from their garden. When Lera and Renaz’ friends came by later that evening, we were pleasantly surprised that instead of vodka, everyone was having tea and shisha.

The next morning we were treated on Blinis (buckwheat pancakes) from Lera’s aunt, after which we were dropped of at the bus station to take us back to the motorway. Here we had our first panic-attack: Jeroen couldn’t find his passport. Renaz and his friend Alina raced back, while Lera tried to convince the bus driver to wait just a few more minutes, when to our great relief Jeroen found his passport tucked away in a small inside compartment of his backpack. After a couple of good-bye pictures, we continued our way east.

From a deserted petrol station we were then picked up by Kamil, who dropped us off at the exit toward Ufa, and showed us in the translation app of his tablet what we have experienced during our trip as well: “All people are inherently good. Sometimes they do bad things, but I still try to see the good in them”. The motto was confirmed not long after, when the cctv camera installer Evgeny took us in for an 850 km drive to Chelyabinsk, only stopping to treat us on Borscht or to show us nice viewing points, although we couldn’t actually see that much, as it was pitch-dark in the middle of the night. While we were trying to teach each other some English and Russian, Evgeny called his wife to organize a train ticket for us to Astana in Kazakhstan. Every week Evgeni drives thousands of kilometers around Russia, which is hard to comprehend when you are from a country as small as the Netherlands.

Not only the size of the country is impressive, the rivers (such as the Wolga) are huge as well, but they all pale in comparison to the size of the Russian women’s high heels. How they effortlessly walk around in shoes with 25 cm heels is beyond us. We spotted only one shoe-related accident, but it didn’t stop the girl in question to bravely continue limping forward in her fashionably high heels.

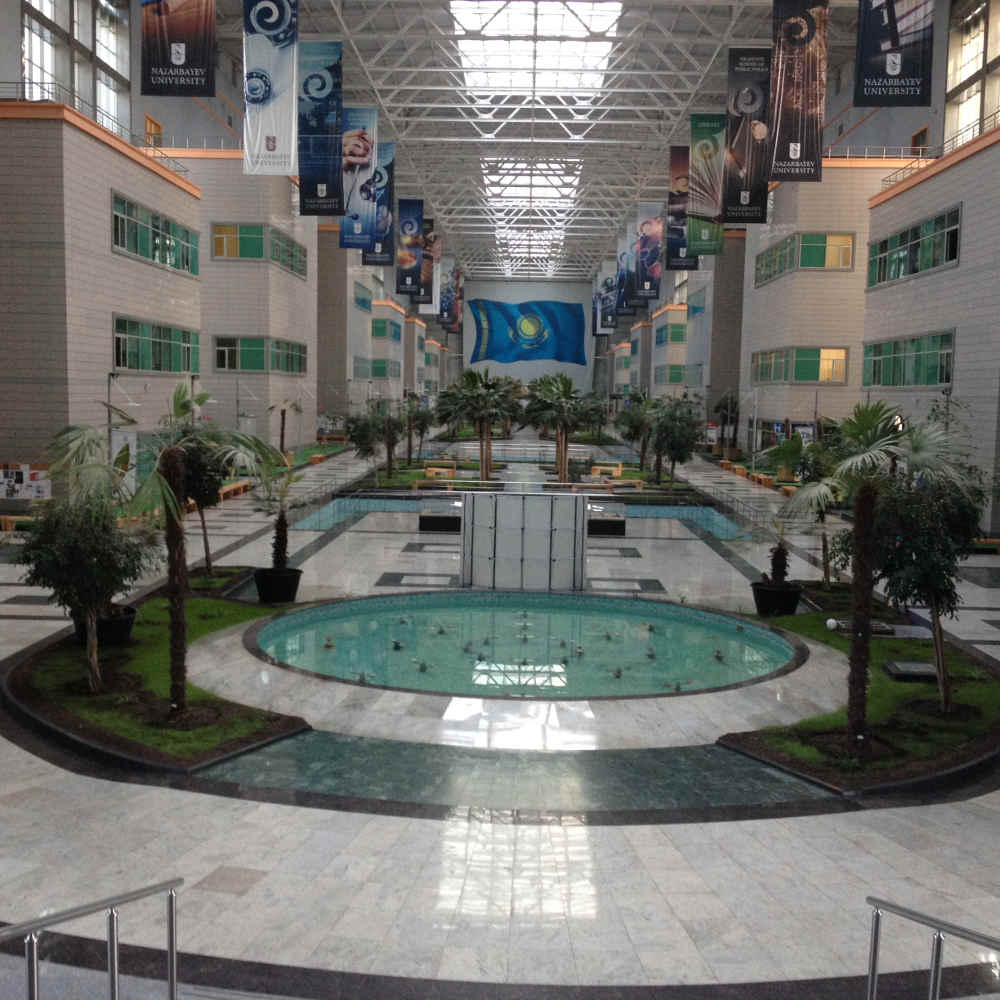

In contrast to this self-inflicted torture, widespread among Russian women, our stay in the train to Astana was most enjoyable. We spent most of the 1000 km laying down, catching up on some sleep, while enjoying our view of the vast Kazakh steppe. In Astana we found our way to Sergey and Nathalia, who introduced us to the incredible Kazakh hospitality by not only offering us a place to sleep, but also by showing us around the city on bike. The city is an architectural playground, with many exotic buildings scattered across a Soviet-style infrastructural city, which was nothing but steppe before it was made the new capital city of Kazakhstan about 15 years ago. In winter, the temperature can drop to below minus 40 degrees Celsius and during snowstorms, the police closes down the city to prevent high-risk and costly rescue operations from people that get stuck in the snow. Something that was hard for us to imagine, while cruising through the city in our slippers and t-shirts. It didn’t turn out to be our last taste of the Kazakh hospitality.

As we continued our journey, we noticed that another pronounced trait of the Kazakhs is their curiosity. Many drivers, even those who were going in the other direction, stopped to ask us what we were up to. Fortunately, we’ve learned by now how to explain our travel plans in Russian. Not soon after we were taken in by a driver who was incredibly friendly to us, until he suspiciously asked whether we were “globalization agents” and proceeded to express strong nationalistic tendencies as well as his rather pronounced homophobia. We felt somewhat flattered to be seen as agents, but were also a little sad. To Europe he would not want to travel, since all people were gay. In addition, the Netherlands is a drug-infested country. We decided to think of Kamil’s motto: “All people are inherently good, but sometimes they do bad things…”.

Our driver tried to convince us not to continue on our planned route along small roads, but to go with him to the closest bigger city, as there would be more traffic. But we were looking for adventure and decided to try our luck. After waiting for half an hour at the crossroads of a dusty road and not a single car passing by, we slowly lost heart. We had some entertainment though, with a stranded bus on the side of the road full of curious Kazakhs who, after some hesitation and initial reluctance, decided to come over and ask us about our trip.

Fortunately, one of the many small police stations was located near by, so we walked up to one of the police officers. We learned that our preferred route was not so bad, but with a desperately gesticulating “nje machina” (no car) we made it clear that we had been rather unsuccessful thus far. The friendly policeman then offered to drive us over the deserted road to a better crossing. After a few unsuccessful attempts he managed to get the engine going and so we drove with blue lights further in the direction of Pavlodar, cheerfully waving at the guys of the bus

The new intersection also lent itself much better for hitchhiking and after two short rides we got in the car with Sertay and Alma, who gave us enough experiences for an entire week in just one day, which brings us to our second story of the amazing Kazakh hospitality. Sertay and Alma did not seem to be bothered by our inability to speak Russian and happily chatted away at us. We mostly nodded and smiled, trying to catch a word or two from what they were saying. They invited us over for tea and lunch with their relatives in a nearby village and while we enjoyed the excellent fish, we tried as hard as we could to scrape together the little Russian we know, to try and communicate with them. As we later drove further up toward Pavlodar we passed a group of guys on horses in the steppe. Sertay hit the brakes and drove up to them to ask what they were up to. Immediately we were involved as advertising models in a promotional film for a national park. We were interviewed and asked to say “Kazakhstan chorosho” (Kazakhstan is good) many times. Linda got her head wrapped with a flag of the national park and was then hoisted up a horse, all carefully registered on camera.

When we finally arrived around 6pm in Sertay and Alma’s small village Radnikovsky, located in the middle of the steppe along the Irtysh-Karaganda channel, which supposedly runs all the way from China to Russia, we were even invited to spend the night. Sertay immediately put an end to the last aspirations we had to try and be vegetarian, when he said “bèh” and “shish kebab” a couple of times with a twinkle in his eyes while sliding a finger across his throat. As we tried our best to convince them not to go through so much trouble for us, more and more people from the village came round to have a glimpse at the tourists, word got around quickly. Luckily Gulmira dropped by as well, their daughter in law who spoke perfect English. She took us on a walk through the small village, and told us about her wedding from a few months ago (in Kazakhstan it’s not a wedding unless at least 300 guests are invited) as well as the challenges and beauties of getting used to her new life in the countryside. She also treated us on some kind of horse-buttermilk, which tasted rather interesting and unusual. We both obediently drank up.

When we returned from our walk, Sertay sat calmly on his garden bench and we were already hoping that we had simply misunderstood him. Our hope was quickly shattered when we entered the kitchen with a carved up lamb lying before Alma on the kitchen table. Sertay had probably diplomatically sent us away to not burden the faint-hearted souls of us Western Europeans. We imagined to still see a few hastily wiped away blood spatters on the wall.

So a feast was prepared and a few other people from the village came by to see the new village attraction, according to Gulmira we were the first tourists to have ever visited their village. Alma was running around the kitchen with a dough roller and head scarf in her hair to not only prepare the shashlick, but also a traditional horse-sausage and a Kazakh dish made with dough.

We ate and drank, with the poor Gulmira serving as our translator, as Sertay repeatedly uttered short speeches about friends and hospitality, to which a new glass of vodka was raised each time. It was an incredible party and when we finally went to sleep, Sertay even tried to apologize to us for not finding the time to heat up the sauna.

After a solid breakfast the next morning we were then maneuvered into the bus, because our hosts wouldn’t allow us to simply stand and wait next to the road. Behind the orange curtains we left Sertay and Alma’s family in deep gratitude. We have now arrived in Pavlodar where we were spontaneously invited by couchsurfers Yura and Svetlana and their five cute little kids. Some sleep would be really good now.